The Silk Thread of Gorindo - Ottawa - Canada

Issue V

- The Simple Act of Breathing (Part 1)

- Darkness on the Edge of Town

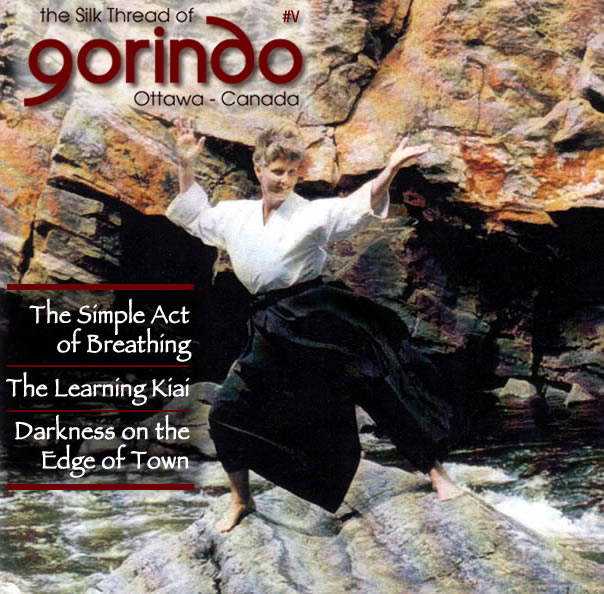

Photo cover Roxanne Standefer sensei, Gorindo School of Martial Art

The Simple Act of Breathing (Part 1)

Each breath we take, from the first to the last, is the very measure of our days. We continuously engage in an exchange with the air around us. Through the process of respiration our organism replenishes its supply of oxygen and rids itself of carbon dioxide.

Breathing is unusual as a bodily function because unlike most other vital processes (the pumping of the heart, the filtering of the kidneys, for example, where the body performs the process unconsciously), we also have a voluntary control over breathing rhythm and volume. We can hold our breath to go underwater, we can exhale to sing a long sustained tone, or inhale a deep lungful of scented air in a pine forest. This is an important area in the distribution of power between the body and the mind; neither is in complete control and the balance is always subject to negotiation.

Why then do we tend to completely ignore our breathing? Unless congested with flu or out of breath after climbing a long flight of stairs, we hardly take notice of our most vital activity.

The martial artist in contrast studies this delicate relationship as a fundamental of training. He practices with careful attention to breathing in order to energize and efficiently utilize the body’s power.

By consciously controlling his exhalations, he can calm the mind and relax emotional responses.

Although we all breathe, we don’t all breathe well. For many, the modern sedentary lifestyle rarely compels us to breathe deeply or rapidly unless we are stressed or angry. Running to the bus stop can put some people out of breath and it is often at these times that one thinks: “Oh, I’ve got to get in shape!”

Even for those already committed to a fitness lifestyle, going for a walk or run along streets congested by the internal combustion engine and construction dust can do more damage than good to the lungs and immune systems.

There are several important considerations in improving one’s breathing. The first is capacity, the actual volume of air that can enter and leave the lungs. Another is the aerobic ability of the system. What is most important about both of these is the actual efficiency of the gaseous exchange going on in the alveoli, the thin vessels deep in the lungs across whose membranes the molecules of oxygen and carbon dioxide enter and leave the bloodstream. This circulation represents the real capacity of breathing to energize, replenish, and refresh the body as a whole.

Early in their training martial artists will learn to inhale and exhale in such a way that maximum gas exchange can take place at the cellular level. Greater control over the mechanism of breathing can benefit technique, timing, and the overall health and strength of the body. Through abdominal breathing, muscles can be alternately contracted and relaxed to maximize breathing potential and provide anatomical support to the body. Expanding the mind’s ability to focus and empty in the same way, is an additional benefit of the exercise of breathing.

In Gorindo emphasis is placed on the slow exhalation phase of the breathing. This promotes the full emptying of the lungs of waste by-products but also prolongs the time that the body is in the exhalation mode. Studies and practice have shown that one is stronger for pushing, pulling, striking, jumping, etc., when breathing out; especially if the breath can be controlled to assist in the timing of an event. Absorbing a blow or maintaining balance is aided by breath control, and an audible shout or kiai is often utilized at the moment of maximum strength or impact.

When frightened or anxious we tend to inhale more rapidly, and holding the breath when startled is common. However, the body’s muscle strength drops rapidly when a breath is held, and the consequent buildup of carbon dioxide in the blood and brain triggers even more anxiety and fatigue. Hyperventilation or uncontrolled shallow gasping for breath can completely short circuit the timing of the breathing mechanism, and bring about a response close to panic.

The martial artist learns to breathe from the abdomen in a manner similar to yoga practitioners, singers, actors, and wind instrument players.

This is also referred to as breathing from the diaphragm. Both these descriptions are somewhat misleading (of course, because all breathing is done with the lungs), but as a mental image, the idea of centering the breath low in the body is helpful in re-training the breathing response.

Children and animals at rest naturally breathe with visible movement of their abdomens, rather than their chests. Adult humans seem to have lost this natural ability, and we can only speculate on the cause.

The ideal body image in the West demands a flat abdomen and well developed upper body, and sadly, fashions which are worn tightly about the waist and hips only help to constrict the breathing. Too much sitting in desk chairs, television couches, and automobiles has certainly debilitated our posture; combined with very little cardiovascular demand for oxygen in these positions, this has likely contributed to shallowness of breathing (and shallowness of thinking, one might argue).

Although a large volume of air will enter the nose and mouth when we take a big breath, only a small portion of this air will travel as far as the alveoli. This is particularly true if the breath we take is shallow and the lungs are not fully inflated. Many people breathe only with the upper portion of their lungs even when engaged in an activity that demands a good oxygen supply. A visible indicator is the extent that the shoulders rise and fall while breathing. The chest cavity is looking for room to expand and shoulder movement will result. This is not, however, the best way to improve capacity, as it still confines the air exchange to a small portion of the upper lungs.

In order to answer the oxygen demands of the body, the rate of respiration (number of breaths per minute) will increase. Normally, this compensation does not nearly fulfill the potential available.

Martial artists, on the other hand, work to control their breathing and expand the capacity of the lungs by strengthening and localizing the response of the diaphragm muscle, in order to allow expansion of the lung tissue down into the abdominal cavity.

The diaphragm is a smooth, thin sheet of muscular tissue that stretches in a double dome shape from back to front across the body, completely separating the thoracic cavity (which holds the heart and lungs) from the abdomen (intestines, stomach, liver, etc.). When we inhale deeply, the diaphragm works to push gently against the abdominal organs, pulling down the pleural cavity around the lungs. The lower ribs swing outward and upward to allow the lung tissue to expand downward into the space created. Most texts on physiology look upon the act of inhalation as the part of ventilation that requires muscular effort and the expenditure of energy. From their point of view, it is exhalation that is the automatic and relaxation phase of the muscles involved.

Martial artists and others interested in working with the body’s breathing mechanism as a tool, train their “instrument” to be used in just the opposite manner. They consider exhalation the working or power phase, with inhalation occurring to restore the relative atmospheric pressure. Taisen Deshimaru, a prominent Zen master, emphasizes in The Zen Way to the Martial Arts the importance of breathing out slowly, with control and always from the abdomen. He maintains that it is vital to good health to train using zazen (seated meditation) in order to make this response unconscious, so that it can be performed when sleeping as well as when physically active. In addition to the calming effect on the mind and the release of tension in the upper body, it is important for the martial artist to realize that he should strike when breathing out, and guard against the vulnerability of the moment of inhalation, a weak point in any defense.

This inhalation can be especially dangerous for the martial artist who is not breathing from the abdomen, or hara. An intake of breath that is too “upward” in the body redirects the attention away from a low, stable center of gravity, and can be all an opponent needs to knock you off balance. Receiving a blow to the chest or abdomen when inhaling can have the disastrous effect of disabling the breathing signal mechanisms, familiarly known as “having the wind knocked out of you.”

Exhalation during a blow and the accompanying tensing of abdominal muscles reduces this effect and protects vital organs. Striking as an opponent inhales is a simple counterattack skill. Learning to read this intention in others is a technique facilitated by observing one’s own breathing, balance, and body language. Even a simple signal such as the flaring of nostrils before an attack gives away the breathing rhythm of the opponent, and watching carefully can reveal a need for oxygen. Movement of the shoulders or chest can telegraph the intention to strike and can be used to fake the start of a technique. As part of the study of tactics, a student of ninjutsu, popularly known as a ninja, learns to breathe silently and without motion of the body for stealth and “invisibility.” The warrior, combatant, or competitor learns to syncopate the breathing rhythm to confuse opponents, preventing them from taking advantage of vulnerabilities. Other metabolic systems of the body are influenced by respiration even if they are not directly controlled by ventilation. The lymphatic immune system operates in the body fighting invading diseases, and although not yet completely understood, its circulation has been shown to be strongly affected by breathing processes. It is postulated that contraction of abdominal muscles suppresses the sympathetic nervous system, having the result of reducing common reactions to stress and fear (increased heart rate and blood pressure), allowing some measure of control over emotional reactions. The autonomic nerve center of the solar plexus is also affected by abdominal breathing. This network controls the digestive processes and waste removal mechanisms of the liver and kidneys by controlling the circulatory ability of small blood vessels and capillaries.

Yoga has a long legacy of belief in and practice of the detoxification and purification of body, mind, and spirit by breathing technique. Chi kung, tai chi chuan, and shiatsu are Asian healing practices that teach breathing as a fundamental basis for self-healing or the treatment of others. Modern movement therapies such as Feldenkrais, Alexander, Trager Mentastics, and Rolfing all have accessed this ancient knowledge for their exercises that coordinate breathing and physical action to improve health.

What then is this abdominal or diaphragmatic breathing?

Excerpt from “The Secret Art of Health & Fitness – Uncovered from the Martial Arts Masters” by Claudio Iedwab & Roxanne Standefer

- The Simple Act of Breathing (Part 1)

- Darkness on the Edge of Town

« Click the Subscribe link on the left